The Provincial Monuments Commissions and their defense of heritage

The custody and guardianship of heritage is a subject that continues to stir up debate wherever there is a monument of historical and artistic value whose ownership and use are not clearly defined. But was it always like this? When did this concern for monuments and their situation begin? Find out below how the

Complex of Monuments of the Alhambra and Generalife became caught up in this conundrum during the last quarter of the 19th century and how it reached a happy outcome when it was made a National Monument.

Confiscations and revolutions

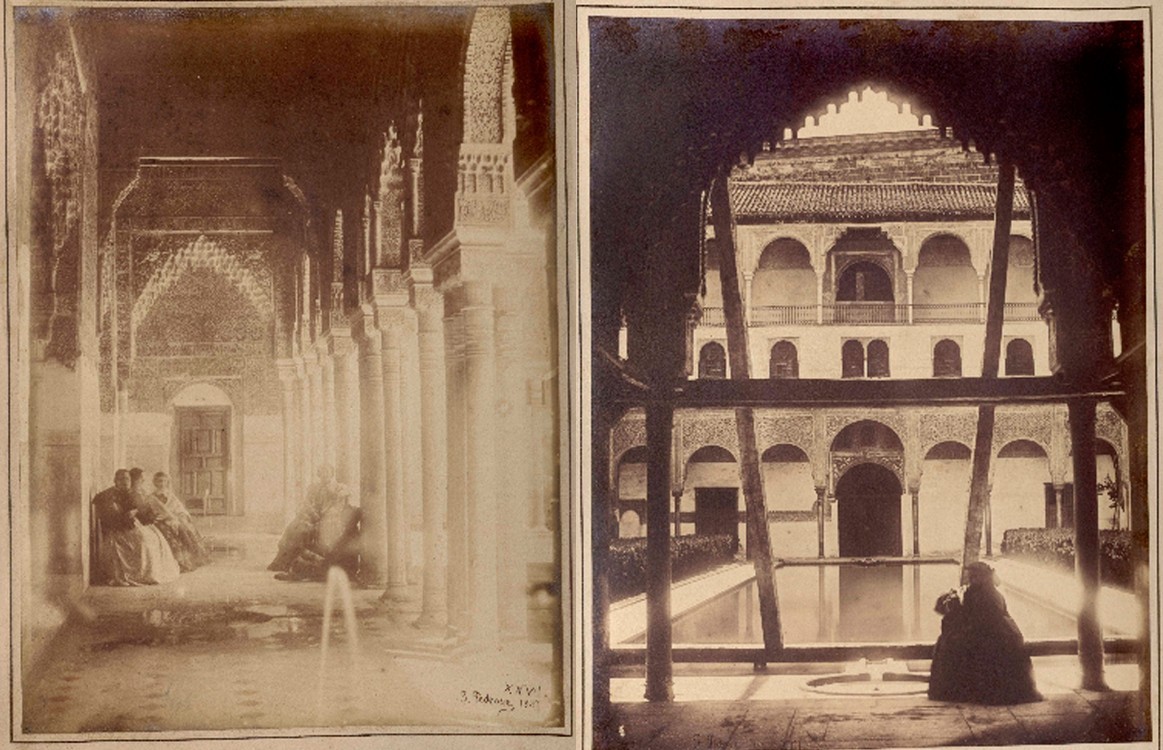

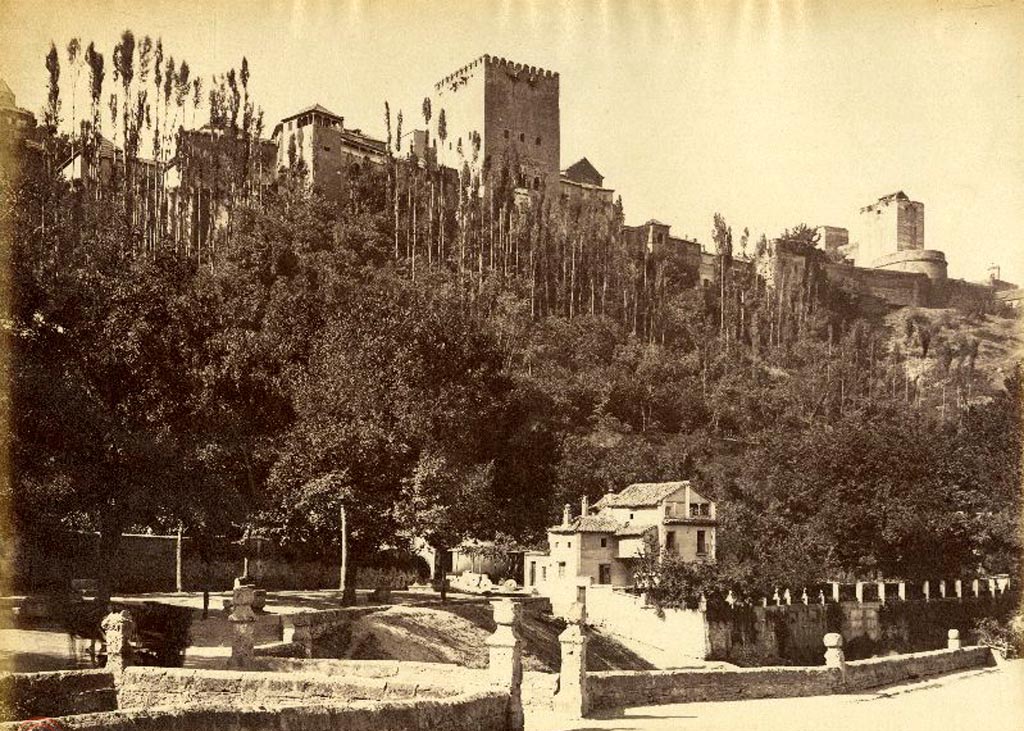

Since ancient times, rules have existed in Spain to prevent or hinder the plundering of artistic assets, but the first solid institutions created to address this issue and manage the inventory and protection of movable and immovable historical and artistic heritage were the Provincial Commissions of Historical and Artistic Monuments and the Central Commission, established in 1844 following the effects of the ecclesiastical confiscations. Although they initially reported to the Ministry of the Interior and the political leaders of each province, in 1854 they were integrated into the Ministry of Public Works, while the San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts took on the task of coordinating the provinces. As a result of the political volte-face that occurred after the “glorious revolution” of 1868, the Alhambra was confiscated from the Crown, ceased to be a royal palace and became state property. The Nasrid fortress and its surrounding territory began a new journey, which would consolidate it as a space open to public use, an emblem of conservation, an increasingly important tourism resource and an administrative symbol of complex management. Concern about the fate of the Alhambra led the Provincial Commission of Artistic and Historical Monuments of Granada to request “the custody and conservation of the Arabic monuments” that belonged to the Royal Patrimony, a request that was immediately granted.

Between two ministries

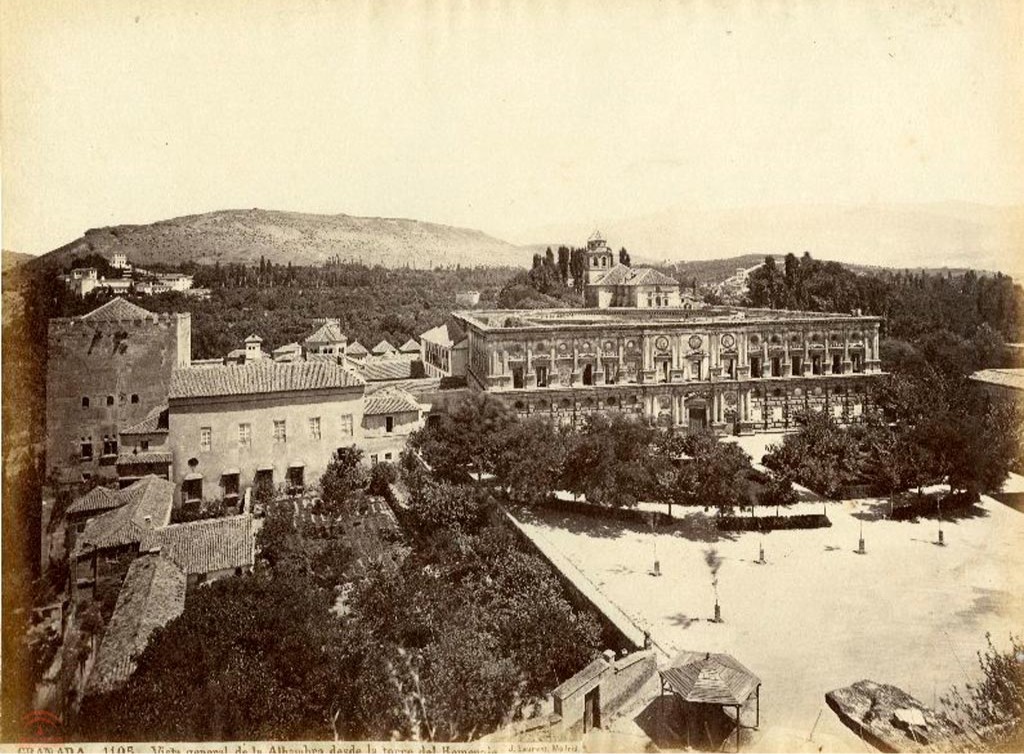

The government tried to rectify the situation by creating a council for conservation, custody and administration. The process was severely complicated by a clash of authority between two ministries, the Ministry of Public Works and the Treasury, who fought over its administration and, most importantly, who was authorised to decide the fate of the estates that made up the walled enclosure of the Alhambra. The council ratified its full jurisdiction over the Alhambra and entrusted it to a Governor-Administrator under the Treasury. The Monuments Commission argued that it only intended to disinterestedly safeguard the complex and took the opportunity to remind all the relevant parties that the inspection and custody of monuments was part of its remit. It insisted that it would ensure that the Alhambra was not broken up because it considered the promenades, gardens, woods and groves to be part of the monument.

Finally, parliament excluded the Alhambra from among the assets established for royal use, raising the spectre of alienation. In April 1870, after several months of uncertainty and accusations, the Nasrid complex was assigned to the Ministry of Public Works via the General Directorate of Public Instruction.

Rafael Contreras, a decorative restorer, was appointed director of conservation and restoration. His resignation as a member of the Commission, due to incompatibility with the post, was never accepted.

At no time did the text of the Royal Order formally state that the Alhambra had been declared a “national historic-artistic monument” or a “historic-artistic monument”, which is how it had been known up until then. Instead, it declared that it was placed “under the immediate inspection and supervision of the commission”, indicating that it was considered a de facto monument, even though this had not been explicitly stated.

This step meant that the Alhambra was no longer a lucrative temptation, although the Treasury retained ownership of several estates that were considered to be productive. The Monuments Commission subsequently appealed to the Regent and to the Academies in order to prevent these assets from being sold.

The new situation and the first audit

The Alhambra was safe from dissolution but the complex process of recovering estates and properties that had been privatised since the Castilian conquest now began. At this time only the Rauda, the Priest’s House, the Partal Oratory and annexed house, and the Ladies’ Tower were available for public use, and not the House of Ayala or the Nasrid armour, which was exported to Germany. In the meantime, the movable assets scattered around the enclosure were gathered together in the modest “Little Museum” and Manuel Gómez-Moreno inventoried the entire historical archive, once it was recovered from the Treasury administration.

Under these new circumstances, the director of conservation and restoration was also treasurer of the Commission, which allowed him to manage the budgets and accounts of the complex under his charge.

The Academy of San Fernando and the government had misgivings about this situation, and appointed a royal delegate to the Alhambra in August 1875. The report prepared by the delegate described anomalies in the management of the complex, irregularities related to employees and the dilapidated state of some areas. It recommended imposing an entrance fee, and outlined a plan to expropriate fifty estates valued at six million reales and fifty properties valued at six million reales. The director responded in a petition, arguing that the private property status quo should be maintained because, the high acquisition cost aside, any change would deprive artists, writers and many distinguished families of their summer retreats and that annual maintenance would cost 125,000 pesetas.

Contreras was aware that the government would have no response to this economic argument and therefore easily passed the first audit, strengthening his authority. The annual plans of works submitted to the Commission were always dominated by cleaning, basic maintenance and, above all, the replacement of decorative features. In turn, the Academy of San Fernando had to report on any submitted projects and it insisted that work on the monument should be limited to simple conservation and consolidation work, and should never include refurbishment or restoration.

Reports and counter-reports

The coronation of José Zorrilla in the Alhambra in 1889 sparked an interest in the monument’s state of conservation and the lack of funds allocated by the government. The incompetence of Mariano Contreras, son of the previous director of conservation, and his opposition to complying with official requirements, led the Ministry to commission Ricardo Velázquez Bosco to report on the real situation at the Alhambra and the actions that were most essential for its conservation. This 1903 report focused on material and organizational aspects, and supported straightforward conservation.

There was political controversy in parliament when members spoke out to accuse the Monuments Commission of being in collusion with the Contreras family and of turning the monument into a life estate. The Granada Commission issued a counter-report written by Francisco de Paula Valladar, which justified its state of abandonment by denouncing the meagre budget allocated for restoring the complex. The Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts personally witnessed the confrontation between restorationists and conservationists during the meeting held with the members of the Monuments

Commission in May 1905.

Bibliography:

Monument and modernity (1868-1936) On the 150th anniversary of the Alhambra as a cultural asset.

Piñar Samos, Javier and Jiménez Yaguas, Miguel. Publisher: Alhambra and Generalife Board of Trustees, 2019.

Contact

Contact