THE INHABITANTS OF THE ROMANTIC ALHAMBRA

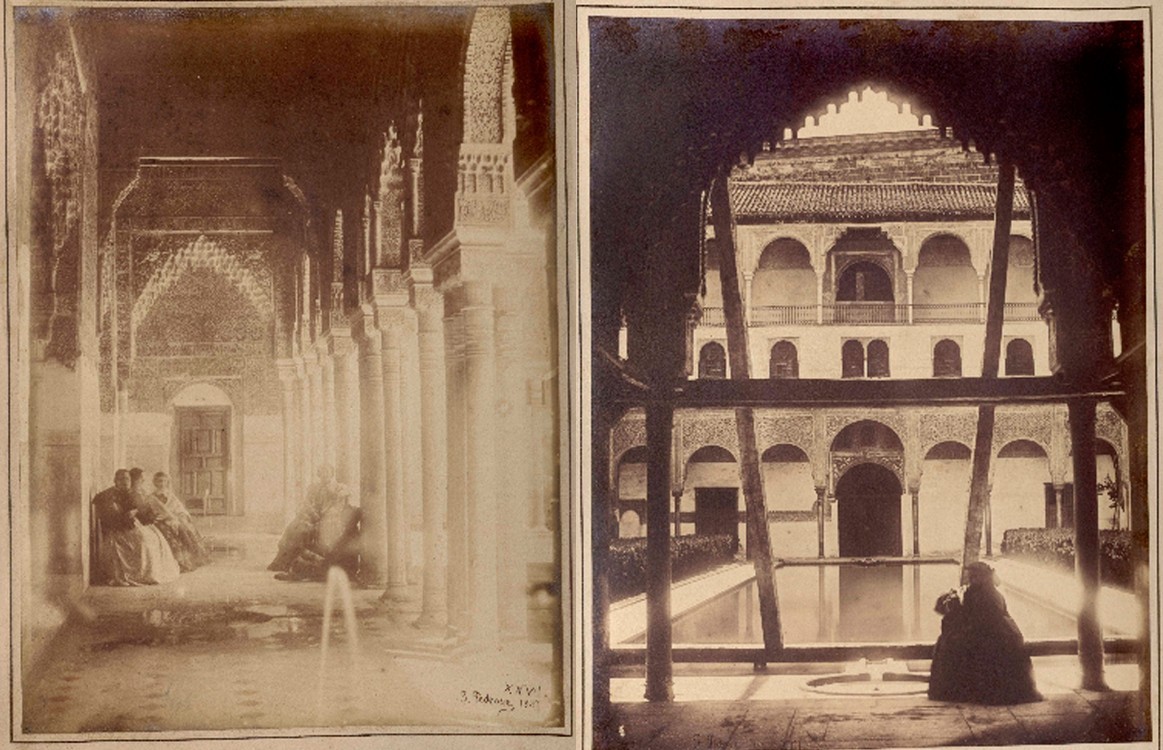

One day when Washington Irving was walking along the walls of the Alhambra, he was surprised to see a man holding a long rod over the edge. Thinking the poor fellow had lost his mind, he went over to ask him what he was fishing for and, to his surprise, the answer was swallows. That would be the man’s dinner, if they took the bait? Most of the inhabitants of the Alhambra lived in precarious conditions and presented an image of humanity that contrasted with the brilliant splendours that romantic travellers imagined at the Nasrid court.

When the former “children of the Alhambra” were able to return to their homes after being expelled by Napoleon’s troops, many found their houses in ruins and were forced to build huts.

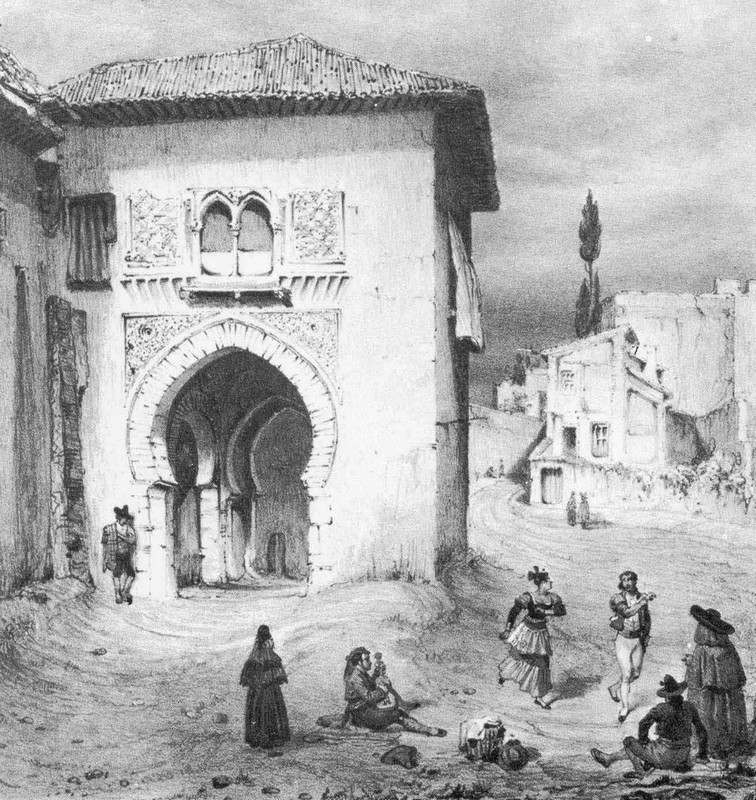

Others were able to repair their homes, which were typically owned by the Royal Patrimony who rented them for very little money and was reluctant to invest in repairs. Most of the houses were located in Calle Real and the side streets leading off it; others were set around large Plaza de los Aljibes. Several towers were also used as residences, including some of great architectural value such as the Ladies, Captive and Princesses towers.

The citadel’s inhabitants numbered around three hundred, excluding the military garrison, prisoners in the Alcazaba and the friars of the Franciscan convent. This is how the most illustrious romantic travellers found the Alhambra, who saw it as a neighbourhood with its own

distinct personality in Granada. In fact, just over half of its inhabitants were born in the Alhambra itself.

Most of the residents worked as weavers and were generally linked to the art of silk-making.

They scraped by with their limited tools and many worked for the cassock factory set up in the convent of San Francisco. However, the convent was badly damaged during the Peninsular War and was finally secularized in 1835. There were also many military widows who, upon the death of their husbands, had obtained permission to carry on living in their homes. The remaining women included laundresses, maids and some shopkeepers.

To supplement their meagre income, many Alhambra residents had small vegetable gardens within the citadel or in the surrounding area, or kept farmyard animals. The archives contain lawsuits that reveal quarrels between neighbours because the chickens of one person

had eaten the crops of another.

Boys and girls went to different schools, which were no more than rooms in great need of repair. The boy’s teacher asked the governor to fix the damp in his classroom, while the girls’ teacher went as far as asking the archbishop to give her a loaf of daily bread and succeeded in making the Royal Patrimony give her a humble house because the monks, ruined by the war, couldn’t pay her.

In the past the Alhambra had enjoyed privileges to encourage the people of Granada to settle in a citadel that was separated from the centre by a steep slope and that, at nightfall, lay in absolute darkness behind closed gates. But little remained of these privileges, an example of which was being able to sell wine more cheaply than in the city. What it did have was a jurisdiction of its own and more lax surveillance.This led to the appearance of lowly taverns in Calle Real where, in addition to eating, gambling and probably prostitution were rife. This

inspired the archbishop to speak from the cathedral pulpit to demand a firm hand against immorality in the Alhambra and afterwards only two taverns were permitted.

There was also a proliferation of smugglers and even deserters from the army who didn’t want to take part in the vain attempts to reconquer America. This exasperated the authorities in Granada, who accused the governor of the Alhambra of turning a blind eye. This

permissiveness may seem contradictory considering that the Alhambra was a military citadel but is unsurprising once you remember that its garrison was a corps of skilled invalids. In 1829 it was replaced by a corps of veterans, soldiers in poor physical condition with paltry incomes who could be bribed with a handout.

The meeting place for residents who wanted to find out what was going on beyond the walls was the well in Plaza de los Aljibes, where water carriers would bring the latest gossip. Pelota was played next to it under a tent made of fabric scraps; the court could be rented and was in great demand.

The main focus of religious activity was the church of Santa María de la Alhambra, where there was a military priest and where various faltering brotherhoods had their headquarters, particularly Jesús de la Humildad y la Paciencia, which brought together the silk workers. The church ceased to be a parish church in 1842 and from then on it was only used occasionally; residents who wanted to go to mass had travel to the distant church of San Cecilio in the Lower

Realejo. It was a symptom of the neighbourhood’s decline and by the middle of the century it had lost half of its inhabitants; even the army garrison was withdrawn and the Alhambra lost its military function. However, an increasing number of travellers visited the Nasrid palaces and the second half of the century was notable for the appearance of inns in and around the citadel. The tourist, the hotelier and the guide would be the new inhabitants of the complex, which was declared a national monument in 1870.

?

Contact

Contact