The gate of Bibarrambla

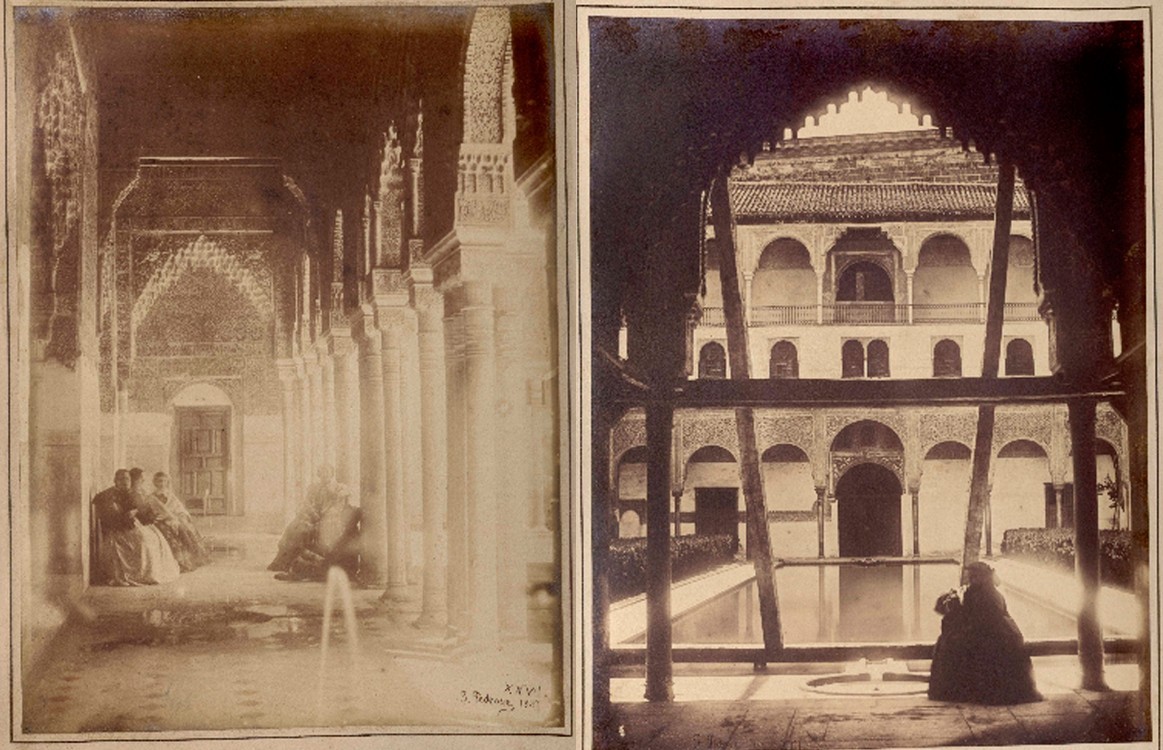

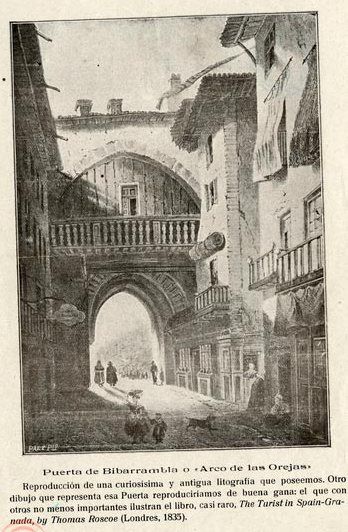

The painter David Roberts visited Granada in the second quarter of the 19th century and of all the drawings and prints he made, there are two that have been more successful: one is the view of the Darro at the height of the Cadí Bridge, and the other that of the Bibarrambla Gate. Both are recognized by all and have been reproduced on countless occasions for being the living reflection of the romantic idea of the Arab Granada.

The Bab al Rambla was one of the main access gates to the city of Granada in the Middle Ages, from the 11th century – the date of its construction – until 1492. After the conquest it was called by both its original Hispanicised name Bibarrambla or Puerta del Arenal (refers to the fluvial deposits of the Darro riverbed, from which it is separated by just a few meters) and by the nickname of Arco de las Orejas (Arch of the Ears) because at the beginning of the 16th century it was home to a flour weight and the mutilated ears of fraudsters were displayed here.

After the conquest it became an emblematic place in the city due to the chapel that was built inside it in 1507, by chaplain of Queen Isabel la Católica ? Bachelor Olivares ? where local residents and people entering the city through the gate came to worship. The monument also nostalgically recalled the past splendour of the Arab period in contrast to a city that was falling into an increasing state of decay as the centuries went by. It was an obligatory stop for the Corpus Christi procession in the Baroque period and a triumphal arch that led to Plaza Bibarrambla when this space was decorated for the bullfighting and cane festivals that were held inside.

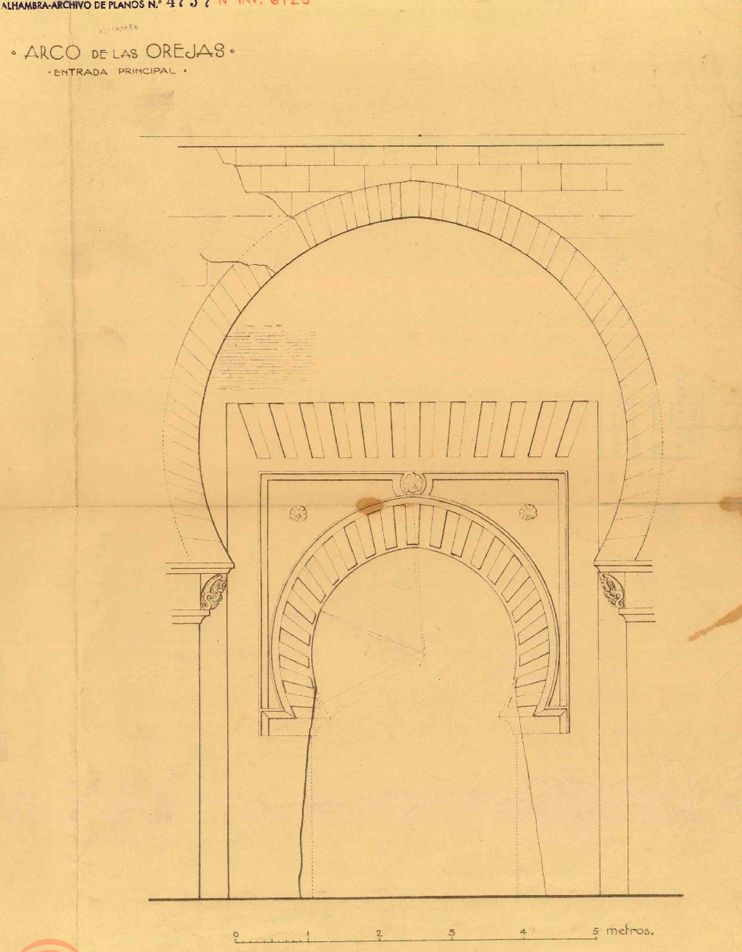

It was formed by two towers that flanked the gate, with a horseshoe arch with shells in the spandrels and in the keystone, topped by a voussoired lintel. This model is very similar to that of the Puerta de la Justicia but differs from the one in that the passage is straight and there is no bend.

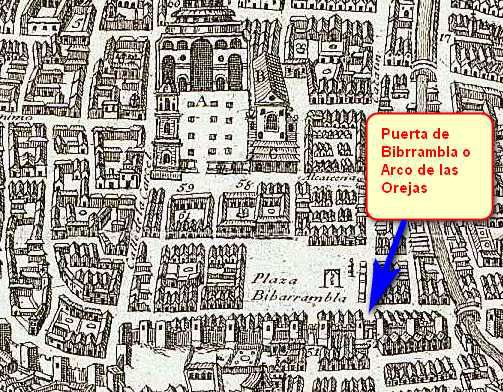

It was straight, with small rooms for the guards, and opened onto the square, also connecting with the artisanal district of the tanners and the nerve center of the medina: Zacatín and the Alcaicería, the shopping area par excellence and the place where the main mosque and the madrassa were located. This gate providing access to the city’s defensive system, the parapet of its walls and the barbican incorporated by the Almoravids in 112-1126 and enlarged in the early 14th century. In the first half of the 14th century a monumental arch was built at the front as a façade, similar to the one that still exists today at the Gate of Elvira.

Until its disappearance, it was located at the confluence of the current Arco de las Orejas streets with Salamanca street, above Monterería street.

In 2016 important archaeological remains resurfaced belonging to one of the gate towers, which were previously thought to be lost, and its connection with the city wall; these were excavated and studied by the Board of Trustees of the Alhambra and Generalife.

Demolition of the Bibarrambla gate and other gates and walls of Granada

It was made the symbol par excellence of Spain and Granada’s Orientalism by 19th century travellers, writers and romantic painters, and also went down in history for the scandalous and lengthy process that led to its destruction. This monument with the passage of time, it undoubtedly became one of the most picturesque monuments in the center because it linked directly with the Islamic past and was the material proof of its existence, praised with longing for nineteenth-century romanticism.

From the middle of the 19th century the zeal for modernisation and notions of greater rationalism in urban planning meant that walls, gates and monuments in Granada were destroyed. Starting in the mid-19th century, the old medieval gates and walls began to be demolished. First the Bibalmazán gate fell, then the Fish gate, the Sun gate and the Iron gate, which was the one that connected Elvira with the Alhacaba slope.

It was the Gate of Bibarrambla’s turn in 1873, when the city council first raised the need for its demolition. Its destruction was initially checked by the Provincial Commission of Monuments and there was an eleven-year struggle between the two institutions, until 1884.

Without exception, Republican municipal governments, revolutionaries of the independent canton and monarchists of the restoration all worked towards its disappearance, while the Monuments Commission mobilised all its influence to prevent it.

The Gate of Bibarrambla was declared a National Historic-Artistic Monument in 1881, but incisive pressure from the local authorities succeeded in demolishing it in 1884.

Reconstruction of the Bibarrambla gate in the Alhambra forest

When the most important remains were recovered, at the request of Manuel Gómez Moreno Martínez and Leopoldo Torres Balbás, the gate was rebuilt in the Alhambra forest in 1933, where it has remained ever since as a further element of the romantic landscape represented by this forest.

The Arco de las Orejas is much more than a nostalgic reference since its demolition between 1873 and 1884 became a symbol of the fight for the protection of Historical Heritage in Spain.

You can learn more about the Bibarrambla door in the publication “The Bibarrambla door” by Ángel Rodríguez Aguilera, published by the Board of the Alhambra and Generalife.

It is also possible to consult this publication in the Library of the Board of the Alhambra and Generalife. Location: CONSULTA 711 ROD.

Documentary and bibliographic sources:

GÓMEZ MORENO, M.; “Puerta llamada de Bibarrambla o Arco de las Orejas”, El liceo de Granada, nº7, Granada , 1874, págs. 97 a 100; y

TORRES BALBÁS, L., “La puerta de Bibarrambla de Granada”, Archivo Español de Arte y Arqueología, nº33, 1935. La aportación más reciente es el estudio monográfico de la puerta:

RODRÍGUEZ AGUILERA, A., La puerta de Bibarrambla de Granada y el flanco occidental de la muralla de la madina hasta Bibalmazán, Granada, 2018.

Contact

Contact