The Alhambra beyond the Alhambra

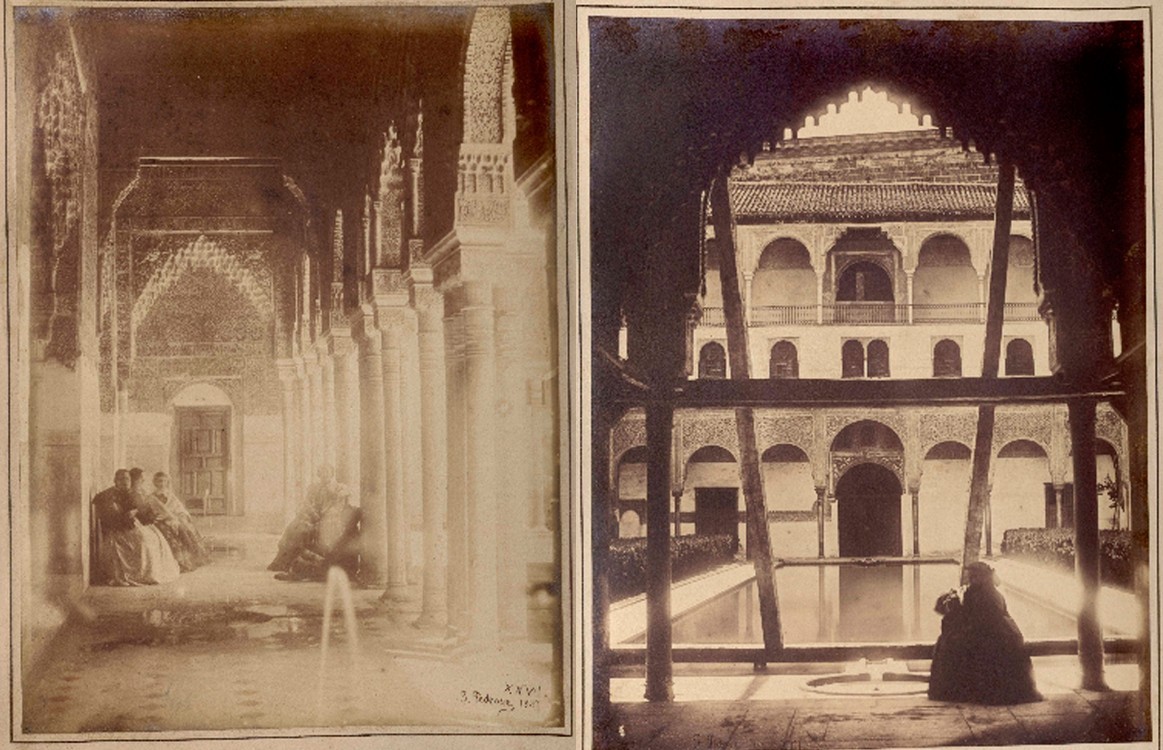

From the moment the Tales of the Alhambra immortalized a lost and rediscovered world, a passion for Orientalism inspired the artistic aesthetic that was known as the ‘Neo-Mudéjar’, the Alhambra being its greatest model and inspiration. A reaction against architectural classicism, among other trends that were interested in aesthetics drawn from diverse origins – from European, Mesopotamian or pre-Columbian roots – gave birth to various eclectic styles and new designs. The Neo-Mudéjar was the result of a fascination with the Alhambra in Granada, the Giralda in Seville, the Great Mosque of Cordoba and other Spanish oriental landmarks. The second version of the Crystal Palace built in Sydenham in 1854 also had a strong influence; inside, Owen Jones built a replica of the Court of the Lions and other spaces

from the Alhambra. Sydenham’s Alhambra Court provided millions of people with knowledge about the Nasrid palace until the Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire in 1936.

In 2017, an exhibition organised by the Board of Trustees of the Alhambra and Generalife entitled “Alhambras: Neo-Mudéjar architecture in Latin America” showed the research results of a team of more than twenty researchers that was coordinated by University of Granada professors Rafael López Guzmán and Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales. The exhibition offered visitors a tour, using photographs, books, postcards and an impressive model, through the rich architectural heritage inspired by the Nasrid fortress that was built on the American continent between the second half of the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century.

Travelers, architectures

Residential, institutional and leisure architecture, buildings whose origins lay in groups of Spanish emigrants, bullrings, the “houses of Spain”, and stand-alone elements copied directly from the Alhambra, abound across the geography of the Americas. They share features with the Orientalist aesthetic developed in Northern Europe but in the Americas, the rise of “Alhambrism” saw contributions from a good number of architects who were trained in and travelled around Europe. The rise of pictorial Orientalism must also be included, and this was conveyed through engravings, illustrations in magazines, postcards and works by renowned painters such as Genaro Pérez de Villaamil and Mariano Fortuny, who were expanding their market in America. These sources were added to by affluent members of society and scholars, who went on earnest educational travels through Europe and knew the English and French Neo-Mudéjar constructions, as well as the Andalusian originals from their obligatory journey

across Spain, Andalusia and Granada.

They sometimes returned from these trips with objects to be included in architecture, such as ceramics or plasterwork, which meant that original elements could be incorporated. All this American heritage is related to the fact that it was usually emigrants – Spaniards, Syrians, Lebanese – who drew on memories of their homeland when they commissioned architects, who had travelled around Europe, to build their homes.

Public and religious building

For example, Owen Jones’s “Alhambra Court” further expanded the proliferation of Moorish pavilions at the Universal Exhibitions. One of the pioneering examples on American soil was

Brazil’s contribution to the Philadelphia Exposition (1876), although the Kiosko de Santa María de la Ribera, Mexico’s pavilion at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Exposition in New Orleans (1884), was far more significant. As Antonio Bonet pointed out, it was about doing something different, fleeing from vulgarity, creating small artificial, almost magical paradises, where the sinful and sultry myth of the Islamic world was a key element. These values should not be confused with the large number of buildings and leisure spaces, from hotels to restaurants, that do not remotely follow any sense of aesthetic intent related to Orientalist or historical culture beyond an abuse of the term and decorative features.

Sometimes Orientalism was applied in interior areas; on other occasions, the focus on the entrance hall was shifted to the exterior of the buildings, where openings and decorative elements emulated Moorish forms. The Moorish Hall of the National Palace in Mexico, the Catete Palace in Rio de Janeiro, or the “Moorish garden”, located in the Legislative Assembly building in Costa Rica, are particularly noteworthy examples of the former. In terms of the latter, fine examples include the building of the Superior Court of Military Justice in Lima, the Municipal Market of Campinas or other public representation such as the Congress of the State of Puebla (Mexico), located in one of the most emblematic Neo-Mudéjar buildings of the city, or the Palacio de las Garzas, headquarters of the Executive Branch of the Republic of Panama.

Religious architecture also gave in to Arabist influence. The Chapel of San José in the Cathedral of León (Mexico) particularly stands out, where the entire decoration of the interior space is infused with the Neo-Mudéjar, as if it were a qubba. Equally surprising is the church of Nuestra Señora del Rosario del Trono in San Luis (Argentina), built on the initiative of the Dominicans.

Finally, there are several examples where Orientalism can clearly be perceived in the building’s interior, such as the Basilica of El Inmaculado Corazón de María in Rio de Janeiro, the Basilica of Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes in Nátaga (Colombia); and the Church of San Juan Bautista in Pasto (Colombia).

Private housing

The Neo-Mudéjar or Moorish style was particularly successful at laying down firm roots in American lands in exotic private homes. These fanciful buildings served individuals as a means of social distinction, especially in residential areas built in the 1920s and 1930s. The upper classes and the new American bourgeoisie did not hesitate to commission these architectural flights of fancy to create an external image of eccentric well-being.

The first Moorish-style building built in Latin America dates back to 1862 and is what is known as the “Alhambra” in Santiago de Chile, a building that today houses the National Society of Fine Arts. It is even more surprising to see this type of construction in countries where Arabic traditions have even less relevance, such as in Bolivia. The Palacio de la Glorieta, a few kilometres from Sucre, is a sort of irruption of oriental fantasy in the heart of the Andes. It wasn’t always the case that the entire residence was built in the Moorish style, sometimes it only left its mark on some of the rooms. This can be seen at Palacio Portales in Cochabamba which has a Moorish-style billiard room.

In the Rio de la Plata region, one such highlight is the courtyard of the Arana residence in La Plata; it originally had a replica of the Fountain of the Lions of the Alhambra that was built between 1889 and 1891. In Montevideo, the Quinta de Tomás Eastman – also called Quinta de las Rosas – and some private residences in the centre of the city are of particular interest.

Although notable private Neo-Mudéjar residences can be found in practically every country on the continent, the Caribbean region is home to the greatest abundance of examples. In Puerto Rico, Enrique Calimano’s residence in Guayama is of great note; it also incorporates a replica of the Fountain of the Lions of the Alhambra that is identical to one that would be built years later in the Casa de España in San Juan.

The most impressive example of Moorish architecture in the Caribbean is located in Punta Gorda, Cienfuegos (Cuba) and is the palace that Asturian-born Acisclo del Valle y Blanco ordered to be built between 1913 and 1917. This building stands out for its remarkable eclecticism, firmly expressed through the origins of its materials, europeans and americans.

Neo-Mudéjar or Moorish style in neighborhoods and rural areas

Although Moorish residences are mostly found in urban areas, either in isolation or integrated into neighbourhoods, mention should also be made of examples in rural areas and private estates far from these centres, such as the now lost Quinta de Agustín Mazza in Argentina, or the hacienda of Mesón de los Sauces, a few kilometres from Los Altos, Jalisco, built in 1881.

The Caribbean is also where remarkable building complexes can be found, such as the Lutgardita housing development in the Cuban town of Rancho Boyeros. In Puerto Rico, the houses built in reinforced concrete in the Bayola neighbourhood in Santurce are another good example. In Santo Domingo, the Gazcue neighbourhood. In Cartagena de Indias (Colombia) the Moorish houses of the Barrio de Manga. Other very localized areas show similar characteristics such as the neighbourhoods of San Francisco in Puebla, Amon in San Jose, Costa Rica, Los Haticos in Maracaibo, El Ejido in Quito, Barranco in Lima, Sopocachi in La Paz, Manguinhos in Rio de Janeiro, and in Medellin and Montevideo.

Bibliographical references:

Temporary Exhibition Catalogue “Alhambras. Neo-Mudéjar Architecture in Latin America”.

Board of Trustees of the Alhambra and Generalife. Department of Culture. Junta de Andalucía:

“Alhambras. Neo-Mudéjar Architecture in Latin America”. Rafael López Guzmán and Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales.

“The prestige of the exotic. Orientalism in institutional architecture”. Yolanda Guasch Marí.

“Inhabiting fantasy. Residential architecture”. Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales and Rafael López Guzmán.

Contact

Contact