A feminine perspective: where did Nasrid women live in the Alhambra?

Elena Díez Jorge, Professor of Art History at the University of Granada, is researching the mark left by women on Spain’s most emblematic monuments. For more than twenty years she has been searching for women hidden in history to discover the role they played in different historical periods.

The scarcity of data in traditional sources means this is no easy task, but “searching persistently unearths testimonies”. She has also been confronted with the prejudices of people who consider a gender perspective to be irrelevant to history.

The few stories that have been passed down about the life of women at the Alhambra are full of stereotypes and legends; in reality, hundreds of women didn’t live crammed into a single room or play instruments in the nude while waiting for the sultan in the harem.

Integrating women into world history is essential for this history to be completed. Who they were, what they did, what their goals were and how they achieved them are questions that must be asked to create a thorough and objective account of events.

It has nothing to do with “political correctness” or fashion, but rather the need to create a scientific discourse on women beyond myth. Showing them as subjects, not passive objects, of history contributes to a re-reading of historiography and transforms society.

This article examines the Alhambra to learn about the women who inhabited the monument in the Andalusí period.

The Harem

The harem has been the female space that has aroused the most interest. In contrast to the romantic and Orientalist legends that described the harem as a paradise full of women dancing or playing instruments, Elena Díez reveals a harem that was far more political than literary.

While it is true that it was a predominantly feminine space, it was far larger than often imagined. In fact, there were probably several harems, not just one. Women of royal lineage, sometimes from different noble families, lived in various different harems. Their power is reflected in these rooms. The harem was not a single room in which the women lived together in overcrowded quarters, but a whole group of rooms, some of which were located on the second floor of the most important palaces.

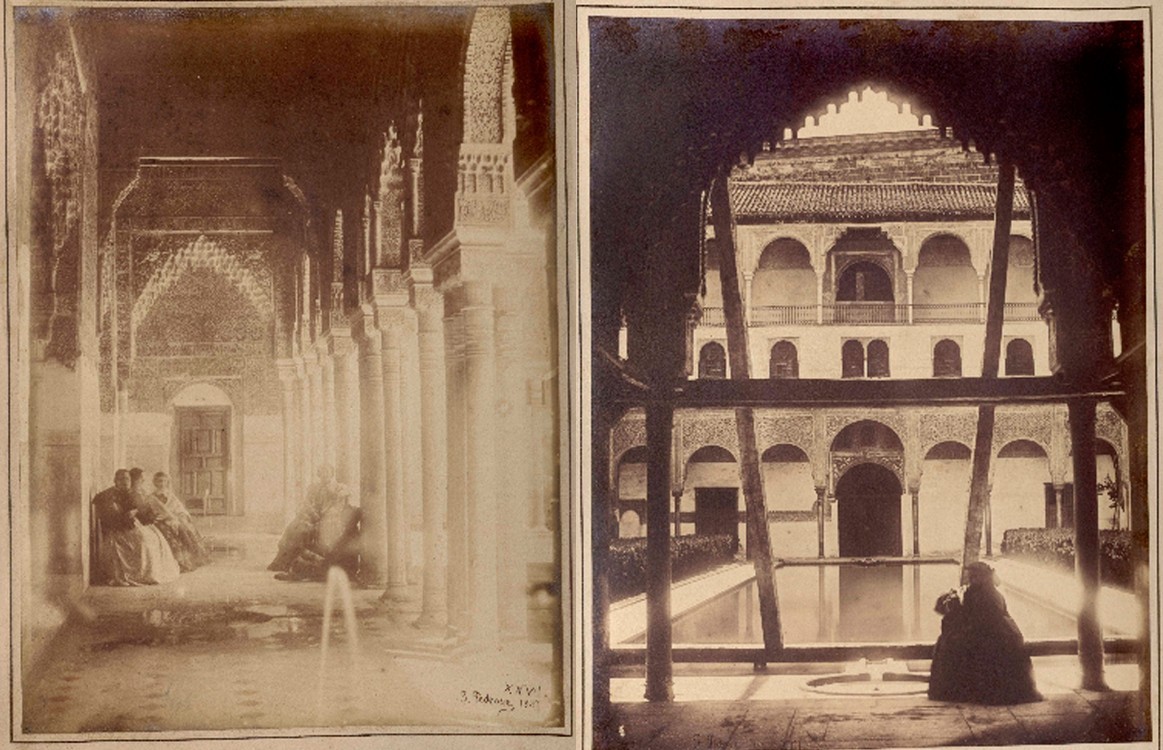

For example, the upper rooms of the Courtyard of the Lions were intended for domestic and probably female use; this is where the Harem Courtyard is located. Its character as a private space that was more closed off from the public sphere can be seen in its decoration: the dado painted in red ochre is far less ostentatious than spaces with extensive tiling or impressive plasterwork. The simple capitals of the columns are also repeated, which would have been avoided in a public space.

The harem was not exclusively inhabited by women, and their sons and daughters (including the future prince in his early years), other relatives, some servants and eunuchs also lived here. The eunuchs were responsible for handling the women’s political affairs in the outside world. However, it should be noted that Orientalist images of the eunuch have also been created that were far from accurate. Apart from the eunuchs, only the men of the family could enter the harem, preserving the women’s honour.

Díez Jorge believes that the harem space has been unfairly treated by historiography. The female occupants are branded as being passive and idle, constantly embroiled in plots, lies, rumours and conspiracies. This was not the case.

Language can be very patriarchal. Power shifts orchestrated by men are called “political strategies” while those organized by women are condemned as “conspiracies” born out of romantic jealousy.

This makes it even more important to point out the political and social work these women performed from the harem. Instead of being secluded and passive, they expressed their power within the gender role they were assigned. For example, they used the eunuchs to develop their plans, and controlled the public life of the palace through the latticework that connected their rooms to the halls of government. This meant that they could observe without being seen, and use the information they obtained to plot their political strategies.

Partal Gardens

The Partal Houses are another space that was probably female at some point; this group of four 14th century houses is located between the Partal Portico and Comares Palace.

These royal buildings are far more private than other Nasrid palaces and have no interior courtyard or great decorative or scenographic schemes. They form a private space reserved for family life and, almost certainly, for women.

The Nasrid paintings featuring human figures and motifs of hunting, war and plunder preserved inside this space are particularly noteworthy. These paintings clearly demonstrate that people were depicted in Andalusian art; women are also portrayed here playing instruments next to the tents.

A text by Ibn al-Khatib (Al-Lamha al-badriyya) mentions a space that could be identified with the Partal Houses. It is described as a place away from the formal areas, near the palaces of Muhammad V, where women resided. The text explains that it was where the sultan banished his brother Ismail who “took on an effeminate character” due to living with the women.

Sources of information.

DÍEZ JORGE, Ma Elena. Mujeres y arquitectura: mudéjares y cristianas de la construcción. Granada, Universidad, 2nd revised and corrected edition, 2016. ISBN: 978-84-338-5964-8 (pdf)

Find out more about Elena Díez Jorge:

Elena Díez is Professor of Art History in the Department of Art History at the University of Granada. She is an active researcher in the field of multiculturalism in art, especially the Mudejar period, and also the history of women, such as her work that examines architecture from a gender perspective.

Contact

Contact